[This is the “One of Our Own” feature from the Winter 2020 Issue of Two More Chains.]

He’s Spreading the Word on ‘Stop the Bleed’

By Alex Viktora

You don’t want to confuse Brian Kliesen with Dracula, but this guy knows a whole lot about blood—how to keep it in you, not take it out.

As the Supervisor of Santa Fe Helitack, Brian oversees the ten-person helicopter module based in Los Alamos, New Mexico on the Santa Fe National Forest. He also serves as the Forest’s EMS Coordinator.

Brian has worked on helitack crews in Wyoming, Idaho and California after starting out on trail and engine crews in Colorado.

As a National Registry Emergency Medical Technician and former U.S. Army Reserve Combat Field Medic, Brian brings a diverse background to medical training. Finishing as a Staff Sergeant in the Army Reserve in 2018, he worked at Army clinics and hospitals at Fort Riley and Fort Hood, as well as in the field supporting training, weapons ranges, and exercises.

He also served overseas briefly with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees. For seven seasons, he worked for Raytheon Polar Services in Antarctica as a Helo-Tech, as well as for several medical-based Non-Government Organizations in Africa, South America, and Asia.

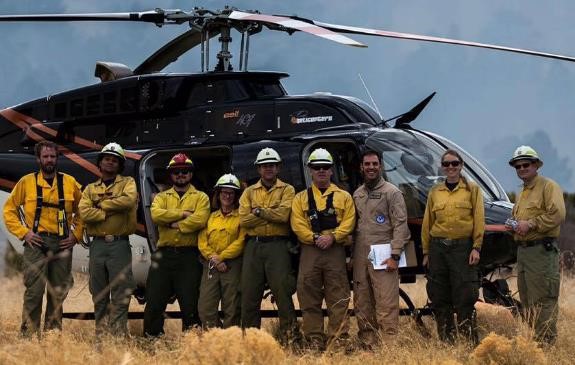

The Santa Fe Helitack Crew in the spring of 2016. From left to right: Crewmembers Dan Sebern, Dijon Clay, Lucas Vega, Margot Jennings, Gehrig Browning, Supervisor Brian Kliesen, Pilot Ben Frisius, NPS Lead Crewmember Bonnie Bolser, and Espanola Ranger District FMO Jon Boe. Photo by Evan Welsh.

Alex: What motivated you to start the “Stop the Bleed” program?

Brian: The Santa Fe and the Carson National Forest train together in the early season as we are a combined fire organization. We spend three days with all the firefighters from both Forests. And we also invite our cooperators, the BIA, BLM, local volunteer, city, county, and state fire departments. We do a lot of the basic early-season training, policy and safety briefings, weather, fire outlook, chainsaw, updates, leader’s intent, aviation and equipment.

This last year, we hosted an hour-long “Stop the Bleed” class. There are several national Stop the Bleed programs that are out there and ours is very similar. We simplified the course based on the Combat Lifesaver Course that I taught in the Army.

It’s a very basic skillset for all firefighters and field personnel: How to recognize severe bleeding and how to stop it using a tourniquet. This provides time for an individual to see the injury site clearly and see if it can be converted to a pressure dressing—and if the pressure dressing isn’t working, you put the tourniquet back on.

I was lucky to have four of my U.S. Army Reserve medics from the 491st Medical Company in Santa Fe participate last year. And because we also invite folks from the municipal, city, and county fire departments, we had quite a few paramedics and medics who were able to help us with this training. This program is very basic. While there are other training programs out there that are probably a lot more involved than what we’ve developed, ours provides the basic skillset that we’re looking for in our line of work. And it’s not just for firefighters.

Non-fire personnel can also benefit from this training who use tools, equipment and chainsaws. That’s one of the things that we’re trying to address by making small, individual trauma kits available to other field-going personnel in trails, range, recreation, archaeology, or any field staff (see photos below). We realize that it could be one of our employees, a member of the public, or one of our cooperators who gets injured.

Alex: Can you talk about the specifics of this training?

Brian: First, we discussed how to use the equipment—to make sure that everybody was on the same page. Then we divided into smaller groups to give everyone an opportunity to utilize the two different types of tourniquets that we use, the C-A-T (Combat Application Tourniquet) and the SOF-T, as well as the Emergency or Israeli Bandage, with a medic to offer instruction and answer questions.

We went over recognizing a severe bleed, and when and how to use tourniquets on arms and legs. It’s really an opportunity to give everyone a chance to get some hands-on training, utilize the equipment, and see how it’s done. After about an hour, we finished with a 10-minute question and answer period and closed by going over the procedure one more time.

This year as part of the three-day Northern New Mexico Fire Summit coming up in April in Santa Fe, we’re going to present the same program. We’ll take the EMTs and those with the more extensive medical backgrounds and talk about going beyond tourniquets—including wound packing and using different methods for where a tourniquet is not appropriate. During this time, the other participants will learn about the tourniquets and emergency dressings.

Alex: How did you get your supervisors and leadership to support this kind of training?

Brian: The leadership here on the Carson and Santa Fe has been real proactive when it comes to training.

We all remember the Andy Palmer incident in which Andy was struck by a tree and basically bled out before they were able to get to advanced medical care. In 2018, I was on the Ferguson Fire in California at Yosemite where Brian Hughes, the Arrowhead Hotshot Captain, was struck by a tree and killed.

It seems every year or so there’s a serious injury or fatality where you wonder if people had this advanced training, if maybe that would have made a difference. Of course, a lot of times it wouldn’t.

With my military training and background, it’s a basic skillset. Every soldier, every person in the military, receives that same training: How to recognize a severe bleed, how to do self-aid or buddy-aid where they can do it on themselves or to their buddy.

We have EMTs in the Forest Service and the Region developing an EMS program where we’re going to have recognized medical direction and control and some standard operating procedures.

So basically, my crew and I were talking about it one day, and I just went up to our leadership at the fire staff level and said, “Hey, I want to put on a class.” And they said Okay. So we pulled this together pretty quickly last spring and presented at the Fire Summit we held here in Santa Fe.

TOP AND BOTTOM PHOTOS – This is the Small Trauma Kit Brian refers to that he’s designed to carry on a pack or saw chaps. This kit contains: Exam Gloves x 4 each, Lg and XL; Trauma Shears; Survival Blanket; 1 roll 4-inch Kerlix; 2 6-inch Israeli/Emergency Dressings; 1 C-A-T Tourniquet; 1 Sharpie and the Medical Incident Report. “We didn’t include the Combat Gauze due to cost and expiration,” Brian informs, “although that is an option.”

Alex: Can you describe these individual first aid kits that you’ve put together and explain how they are different from the typical basic first aid kits that most wildland firefighters carry out on the line?

Brian: The basic first aid kit that’s available from the USFS cache, the red belt pack ten-person first aid kit is essentially useless. It contains some Band-Aids and a few basic things. It’s more of an OSHA requirement. The majority of the first aid kits that the Forest Service has, those large and medium-size metal kits that you hang on the wall or  are in a vehicle, those also fulfill an OSHA requirement. But they aren’t necessarily very useful.

are in a vehicle, those also fulfill an OSHA requirement. But they aren’t necessarily very useful.

After our training, many of the Districts came up and asked: “Hey, can you suggest or recommend where we can get these items?’’ So I created a list of items that were available on GSA Advantage and pointed out this is where these items can be found.

We also identified a squad level or a crew kit that’s specifically for trauma that is available on GSA Advantage and we also built a smaller kit you could carry in the field with you, something lightweight that you can put on your chainsaw chaps or strap onto the side of your line gear of a backpack. Neither kit has Band-Aids, aspirin, or moleskin. It’s designed for trauma, when somebody has a significant cut, a crush injury, a burn injury, something like that.

Many on the Carson and the Santa Fe are now carrying both these kits—and we’re building more. The larger kit is still easy to carry, can be attached to line gear or used as a waist pack and would probably be carried on the engine or perhaps taken with the crew if they have to hike into a project site or fire. The smaller kits are lighter and have two emergency (or Israeli) dressings, a roll of kerlix gauze, a C-A-T tourniquet, exam gloves, a set of trauma shears, an emergency blanket, and a roll of tape.

And we’re now working on building the Medical Incident Report and a patient contact report into one sheet. So one side’s the MIR and the other side’s the patient information sheet. This will be included in those kits, along with and a sharpie, a black magic marker. Nothing in the kit has an expiration date.

TWO TOP PHOTOS – The North American Rescue Squad Kit. This is the larger kit that Brian refers to. He had them remove the chest decompression needles because “they are beyond our level of training.” He explains that this also reduced the cost of the pack when ordering it direct from the manufacturer. This is what Brian is trying to get on the engines on the Carson, Santa Fe and Gila Forests. He reports that, to date, these kits are on 75 percent of these Forests’ engines.

BOTTOM PHOTO – Illustrates the contents of the North American Rescue Squad Kit.

Alex: What was your reaction when you first heard about the Pagosa Ranger District chainsaw cut incident last August in which a swamper’s left forearm received a deep chainsaw cut and a tourniquet was used?

Brian: When I read that RLS I was really happy that the guys responded so well. This was one of our engine crews that had participated in our Stop the Bleed training. Initially, somebody else tried to put a belt on as a tourniquet and the guys there identified that as inadequate. Using a belt is a Hollywood thing. So, they removed the belt right away and put a tourniquet  on.

on.

The whole point of a tourniquet—having folks in the field put them in their fire packs, a tourniquet or an Israeli emergency bandage—is to apply it right there at the point of injury. And the sooner you put on a tourniquet, the sooner you’re going to stop the blood flow, the loss of blood. And then you’ve got time to evaluate the injury and decide if you can convert it to a pressure dressing, or if the tourniquet needs to stay on.

We like to teach: “Air goes in and out, blood goes round and round, life is good.” So I was really happy that they recognized and remembered the training because it had been several months before. And it was only a one-hour-long class.

On that RLS incident, everybody paid attention and they knew what to do and responded really well. Ultimately, the individual didn’t suffer a severe injury. They did the proper first aid and got him to the appropriate medical treatment. I think he received 18 staples or something. Today that swamper is fine and his injury seems to be healing well. He’s not going to have any loss of motion, though he might have some scar tissue develop over time. It’s nice when the individual is able to return to work without any loss of range of motion. He’s going to have a very sexy scar and be able to tell that story as a teaching moment. And he’ll never forget how to treat a major bleed if it ever comes up again.

Alex: How do you respond when you hear “liability” and “tourniquet” in the same sentence? What advice do you have for that kind of concern?

Brian: Here’s what we’re up against. For many years, people were taught—and those people are now in the higher positions—that if you put a tourniquet on someone, the expectation is that they’re going to lose the limb or they’re going to lose function of the limb. There is always a chance that something will be used inappropriately or incorrectly, but that comes back to training. If you are away from your basic 911, in a rural or wilderness context, using a tourniquet or pressure dressing can save someone’s life.

We now know through research and through evidence from the military by the soldiers in Afghanistan and Iraq and Africa and the Far East that the whole goal is to keep the blood on the inside instead of the outside.

This last year, we successfully lobbied the national aviation program to require emergency dressings and trauma shears in the first aid kits for all the Exclusive Use and “Call When Needed” Type 2 and Type 3 helicopters. This was a very simple, easy and inexpensive upgrade.

Tourniquets and emergency dressings are becoming more available and the training is out there now where people know that they can put a tourniquet in place, convert it to a pressure dressing, and then remove the tourniquet. If it doesn’t stop the bleeding, they put the tourniquet back on, write down the time so that the surgeons and the doctors know approximately how long that the tourniquet had been in place. Then the medical team can do the appropriate interventions to properly restore circulation.

We know from the military that people have had tourniquets on for 8, 10, 12 hours and they’ve been able to get full or a majority of their function returned to that particular limb. It’s a very effective, very safe way to stop a severe external hemorrhage. However, the thing is that it only works for arms and legs. So a severe cut or injury to the neck or the torso requires other techniques.

That’s another training area that we’re hoping to expand on in this next class at the Northern New Mexico Fire Summit. A lot of the city, county, state, municipal EMTs and paramedics will be there. They can help those individuals or EMTs who would like to learn some more advanced techniques. Like teaching how to respond if the injury is in the chest, or in the abdomen, or the pelvis, or shoulders, or where ever.

Of course, our main focus is on the arms and legs because those are the areas that get hit by pulaskis, chainsaws, rocks, and whatever.

Alex: What kind of advice do you have for folks who might want to replicate—to the extent that they can—the training program that you’ve implemented?

Brian: Nationwide, there’s a very strong push right now for Stop the Bleed programs. You can Google “Stop the Bleed” and you’ll see there are classes that are available where you can learn the basics. The Stop the Bleed programs seem to be popping up all over the place. You can also talk to your local ambulance service, hospitals, or fire department. With so many people with previous military experience who have been exposed to this process, the information is out there.

In addition, many school districts are now providing the training for a mass casualty or a shooting incident. So it’s becoming more common. With the price of tourniquets going down and their availability increasing and with widespread training, I predict you’re going to be seeing this quite often.

It is a very basic skill set. It’s nothing too difficult or invasive. It’s just like with any other skill, you learn the basics and then you practice it so that it becomes second nature. Then, when you do see an incident or accident where a tourniquet or a pressure dressing is appropriate, you’ll know what to do.

Alex: What advice do you have for somebody who’s freaked out by the sight or the thought of blood?

Brian: That’s a personal thing. There are quite a few people out there who cannot handle the sight of blood. They need to recognize that they have those limitations, but also remember that what’s happening to them is nothing compared to what’s happening to that individual who has the severe injury.

Once again, it all comes back to training—to doing it often enough. They used to call it “muscle memory.” Now I think the term is “familiar task transfer.” There are studies that say you have to do something so many times in order for it to be ingrained in your memory. So, training that you have to do every year helps.

Most people have CPR certification for two years. But, they should really review or go over that stuff every single year, or even more often if they’re in an environment where the possibility exists that they may have to do CPR.

The same applies to a severe bleed. You have to be able to recognize it and respond. If you train often and thoroughly enough—so that training is ingrained in you and you respond quickly—there won’t be as much blood and maybe you can get past that.

But again, it’s all about the training. It’s all about the exposure and sort of getting used to stuff. Some people don’t like to fly, yet they learn over time that it’s safe and they take longer hops and they fly in smaller planes, or whatever.

They get used to it.

Stop the Bleed

Excellent program …Went thru two drills with them with Civil Air Patrol 3 years ago

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have been providing austere medical care for 29 years. I am an emergency physician, former EMT/wildland FF, prior service USArmy physician, SAR member and EMS medical director This is one the most important skill sets every wildland ff should have. Be ready to control bleeding. It can make the difference between life and death. I commend Brian for getting this training to the boots on the ground. Keep up the great work!

LikeLiked by 1 person